Food stamps, stigma, and hard work: the quiet struggles of South Asian America

by APASA Programming Director Yusuf Rahman

Many in the South Asian community have achieved stability that our ancestors were never afforded. Yet, this success hinges on a delicate balance that far too few of us acknowledge. The truth is, the immigrant experience is still marred with challenge—and for people like my dad, it’s made invisible, too.

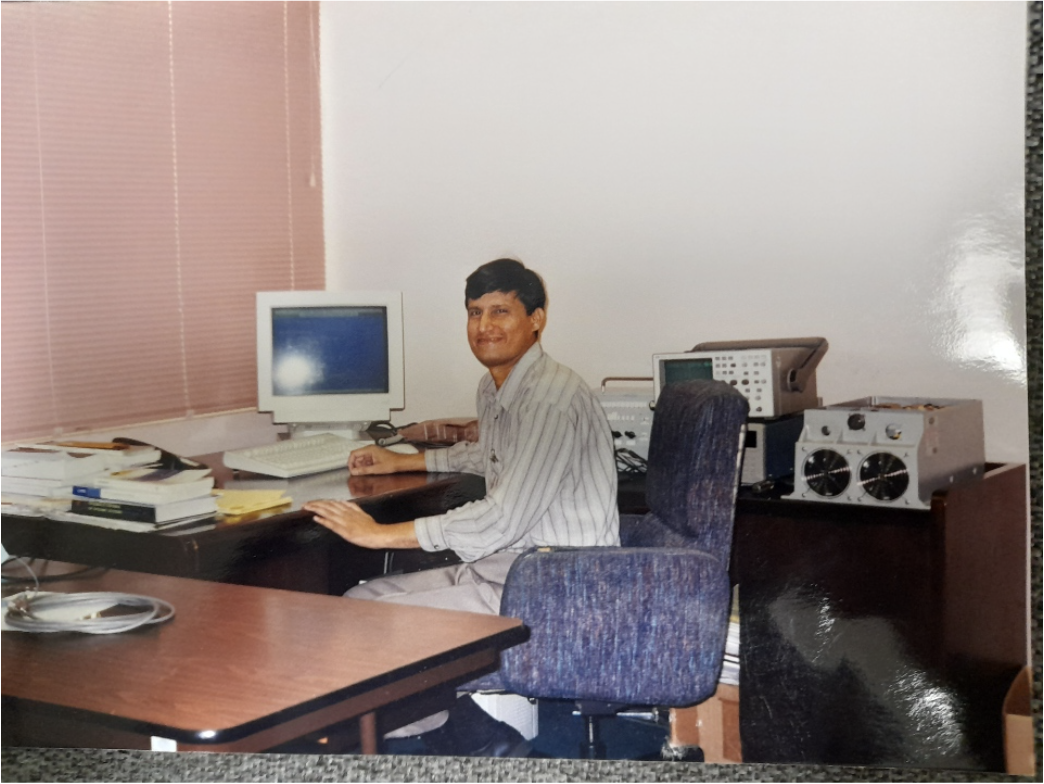

A picture of my dad sitting in his office from 1990-something. He worked as an engineer for a growing firm in the Los Angeles area.

My dad loves telling me the story of how he came to America. It was the mid-90s and he worked as an engineer in Karachi, Pakistan, quickly moving up the ladder. His intellect was lauded by his coworkers, former classmates, friends, family, acquaintances—the list goes on. No one could deny the mark he was making on his company, going on business trips to Switzerland and other countries he could have only dreamed of growing up in the Pakistani countryside.

Then one day, he got a fated call from a close friend who made it out to the States, telling him that his company was looking for a senior systems engineer. The opportunity gleamed. Within months, my dad got hired, got a visa, and crashed at his friend’s place, ready to embark on an exciting new chapter of his life. A chance to help his family, to raise kids who didn’t have to face the hardships he did.

It’s an achievement I personally believe is extraordinary. It’s a stark contrast, though, to when we were standing in line at the social services office trying to get him food stamps last week.

Somewhere along the way, the dream fractured. The company he joined and advanced in started going under, so he turned towards entrepreneurship. His goal to start a successful business never quite took off from the ground, however. The world only got more expensive as bills surmounted and rents increased, and few technology companies wanted to hire somebody they saw as too old for a changing industry.

He was stuck, and I think the biggest pain for him has come from a feeling that he could not support the people who raised him.

My dad’s story is not an uncommon one despite how South Asian Americans have been depicted in popular culture. The narrative is that our quiet, dutiful nature lands us successful jobs in America, and we soon find pristine stability all across the country. Doctors, engineers: these are the fields we occupy, supposedly proving that the American Dream is still real.

What a strange narrative it is then, when you look at the numbers. Yes, Indian Americans have the highest median income of all Asian ethnic groups. But 15 percent of Pakistani Americans live in poverty, well above the national average across all demographics. For the Bangledeshi and Nepalese populations, that number rises to nearly 20 and 17 percent respectively. And even among Indian Americans, poverty is still a significant issue—7 percent live below the poverty line.

Clearly, there are thousands of people like my dad. It’s easy to forget that these issues exist, however, when we remain in our bubbles of affluence. We have become comfortable and assume that individual success means the barriers in this country have disappeared, despite a long and ongoing history that shows otherwise.

Intentionally or not, we have created a stigma around struggle that forces people to live in invisibility. For as many successful South Asians we see in countless industries, there are significant pockets of our community that are struggling to achieve their American Dreams.

And as a result, I think my dad has felt a certain kind of shame in seeking help. When it came to getting him food stamps, for example, it was a months-long battle of convincing him. He had this idea that to seek out governmental assistance would demonstrate a lack of hard work and tenacity.

That’s because as an immigrant, my father experienced a unique pressure to succeed all throughout his 30 years in the U.S. From what he observed, he explained to me that as an immigrant, he felt the need to prove himself to Western society—that as a foreigner, he was just as credentialed and capable as his peers. And when you’re surrounded by people who are concerned with their class appearance for this reason, a special kind of peer pressure arises.

But he pointed out that the pressures are internal, too. If you reach a point so difficult where you need governmental assistance, your struggles are seen as a reflection of not just your failure, but of your family’s as well—of how you were raised, the values you were brought up with, the work ethic you inherited.

It’s saddening to hear this because EBT cards are a lifeline for the South Asian community. In Little Bangladesh right next to Koreatown, where I go to get my groceries, this is especially evident. Most of the customers at these South Asian grocery stores rely on CalFresh to get food for their families while still staying connected to their culture. Yet using food stamps is a very hush-hush matter. From talking to my own parents, there is a pervasive feeling that they will be seen as freeloaders or as people taking advantage of the system. For many, then, it’s easier to forego the public safety net altogether.

After all, the biggest source of support for immigrants to the U.S. is family. The process begins with one person who lands some kind of opportunity in the U.S. The hope is that family members—parents, grandparents, siblings—can come to America as well. This individual, however, has an immense pressure to succeed; if they are not able to prove that they can support additional people with their income, then they cannot bring any of their family over.

When it works, communities thrive and the whole extended family can rely on each other for help if someone were to lose their job or fall ill. When it doesn’t, however, the isolation becomes profound. This is what my dad experienced as he found himself becoming disconnected from his community. We became the ones who couldn’t catch up as his peers excelled.

Even now, the social impact of poverty remains. Recently, I learned that my dad has a growing tumor on his kidney—he’ll need his kidney removed at the very least, as the doctors are still figuring out how far it’s spread. It’s a sobering reality to face as a young adult that my dad’s health is declining, but it’s compounded by the fact that his safety net is incredibly thin. With family thousands of miles away and no real sense of belonging in the states, there are very few people that he can truly fall back on.

This, to me, is the side of South Asian America—and really, of many immigrants as a whole—that we don’t see.

–

On Christmas, I decided to take my dad to a Desi restaurant in our hometown, Torrance. It was his first time eating at a South Asian restaurant in years.

I picked up the tab, and as I signed off on the bill, my dad smiled.

“Isn’t it so weird that you’re the one doing this now?”

I nodded. Perhaps my dad, like many others, won’t quite reach the success he dreamed of. But at the very least, I hope that we can break the narratives that have been constructed about our community and reveal the countless stories like his that exist.